As the novel coronavirus spreads alarmingly through China, with reports suggesting more than 70,000 infected, and the number of fatalities slowly climbing, many neighbouring countries are alarmed. One which is high on the list of potential crisis zones is India, almost as populous as China and considerably less well-organised to cope with a disaster of this nature.

The worst may yet not come to pass. Only three cases of infection have been confirmed in India, whereas Singapore has reported 75, Hong Kong 57 and Thailand 35. Still, there is genuine concern that cases are not being identified and reported accurately. The World Health Organisation has declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, which means any country could be at risk. India, with all its vulnerabilities, could be a prime candidate.

The three cases in India, all involving medical students from Wuhan who are now home in the state of Kerala, are all in stable condition and are being closely monitored, two in hospital isolation and one at home. India successfully evacuated 324 students from Wuhan who are now in quarantine in a detention facility in Manesar, less than two hours from the nation’s capital, where none has so far tested positive for the virus. Some 4,000 people are reported to be under observation at isolation wards across the country, but the number of confirmed cases has remained at three for over a week.

The government has sprung into action and instituted health measures at airports and ports, including entry screening, travel advisories and signages at major ports of entry, with checks of any travellers showing signs of cold or fever. But infected persons could still slip through in the asymptomatic but infectious phase of the illness. One sees very few staff or passengers sporting masks at Indian airports. If a carrier enters any Indian city and mingles normally with people, the potential for the virus spreading rapidly remains high. With one of the world’s highest population densities, especially in urban cities like Delhi and Mumbai, it is impossible to maintain the WHO-recommended three-feet distance between individuals.

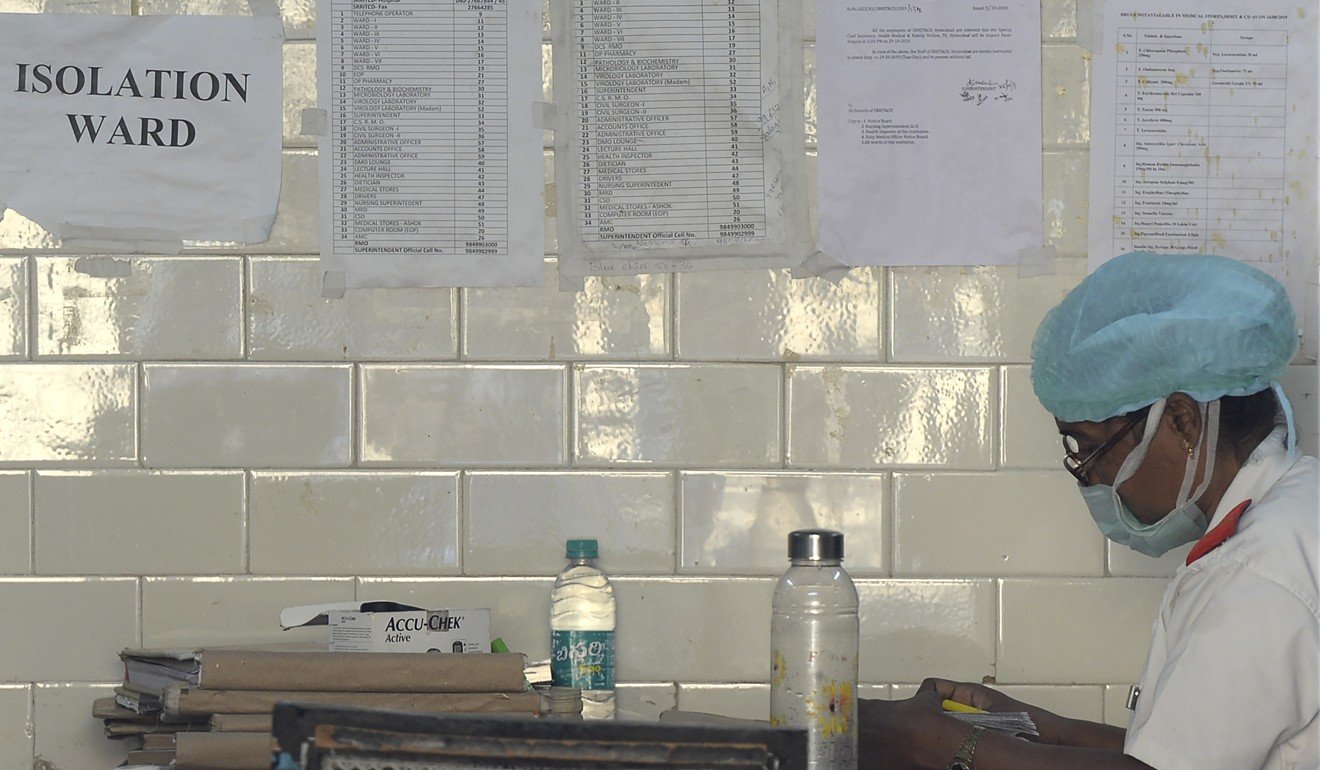

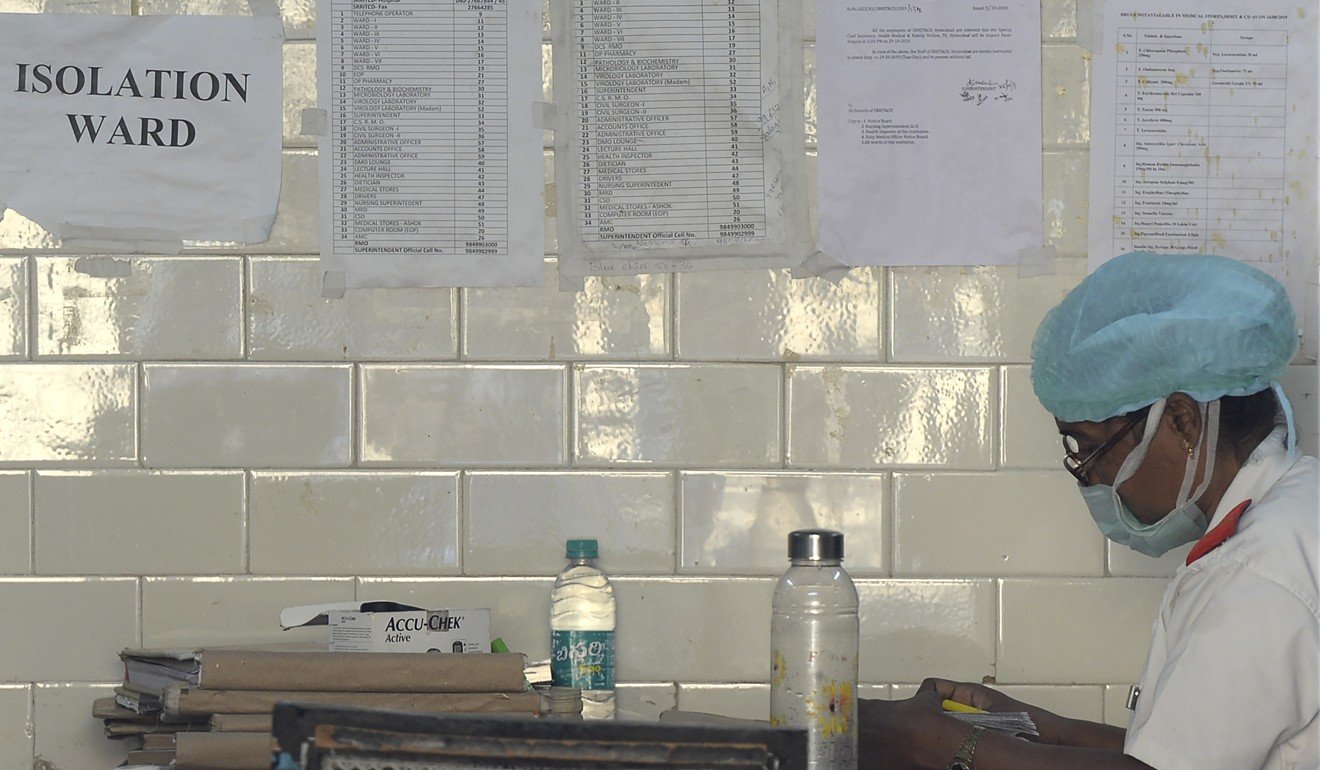

State governments are stepping up preparedness measures. But there are worries about how well India is equipped to conduct disease surveillance, to deploy adequate laboratory testing capacity, to elevate hospital preparedness including infection prevention and control, and to communicate effectively to the public. Indians talk with astonishment and admiration of how China built a 645,000 sq ft emergency hospital in Wuhan in just 10 days, something we would be unable to do in a year. India’s hospitals are overcrowded and overburdened with little scope for a sudden influx of highly contagious new patients. Public awareness is minimal, and no precautionary guidelines have yet been issued to the public by the Indian authorities, in English or in local languages.

There is no comprehensive nationwide surveillance system in place.

Lab testing facilities are few and far between: though facilities were expanded since the H1N1 (swine flu) virus threat arose a decade ago, samples from Kerala are being sent to a virology lab in Pune which remains the only one in this vast country capable of testing for the virus. Against a 2012 proposal to set up 150 diagnostic and research labs with virological expertise, 80 are in various stages of operational readiness, a grossly inadequate number for a population of 1.3 billion. These are also not all linked to the public health response system.

Though India has fairly well-established programmes for monitoring zoonotic diseases like rabies, brucellosis and Japanese encephalitis, it is largely unprepared for the threat of newer viruses, and it was lucky that swine flu and bird flu did not take a higher toll. There is simply little or no integrated epidemiological surveillance of zoonotic pathogens in forests, close-bred veterinary clusters and human population groups, the likely source of the new coronavirus.

India does, however, have a success story in Kerala’s handling of the nipah virus, which claimed 17 lives in 2018. The lack of virological and taxonomic studies on native bats in Kerala made it difficult to understand the nature of the virus, which came from fruit bats. However, the state has learned its lessons well from handling that tragedy, which it prevented from spreading farther. Today it has kept over 2,000 people, who may have come into contact with any of the three confirmed coronavirus cases in the state, under surveillance at their homes. Some media reports claim that families of those who have returned from China have been shunned by friends and neighbours fearful of catching the infection.

However, not every state is like Kerala, and an outbreak almost anywhere else in the country is unlikely to be countered by an agile response system, adequate primary health care facilities to conduct the needed clinical assessments, sufficient lab capacity or effective isolation practices. A serious virus epidemic on the lines of Wuhan would have a catastrophic impact on the country. Indians have been lucky so far that the suspected cases have been few enough to be manageable. We are all hoping that it stays that way.