The country, and the world, have woken up to Rahul Gandhi amid a surge of revivalist enthusiasm in the party he is all set to lead, the Indian National Congress.

His every utterance on social media is followed, retweeted, re-posted. His witty one-liners—“Quick, Modiji: Mr Trump needs another hug!”—are getting people to laugh along with him and against the so-far sacrosanct prime minister. The ‘Pappu’ jokes assiduously pushed by legions of BJP supporters on forums like WhatsApp have dried up, or if they are still being generated, they are no longer acquiring any virality.

Instead, reports speak of ecstatic crowds thronging his rallies in Gujarat. Old timers speak of being reminded of the adulation his illustrious grandmother, Indira Gandhi, used to attract.

Rahul Gandhi is on the rise, and India is sitting up and paying attention.

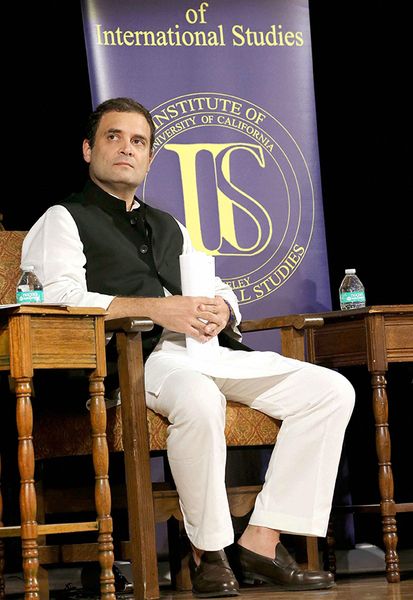

It all started, many say, with a game-changing trip to the US this summer, when Rahul Gandhi shed his old reticence and interacted effectively with a variety of audiences, from university students to Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and Washington Post journalists. I was in the front row of his audience at Berkeley, and can vouch for his successful rapport with a standing-room-only crowd, made up mostly of students of Indian origin. He came across as clear-thinking and comfortable in his own skin, as well as a good judge of his audience. It was here that his frank and unapologetic answer on political dynasties earned both applause and approbation.

But I believe the renaissance of Rahul Gandhi actually started a couple of years earlier, upon his return from a vipassana sabbatical in April 2015. I remember how at that time “RG” (as he is often referred to behind his back) hit the ground running. The morning after his arrival in Delhi, he addressed a kisan rally. Within days he was showing a penchant for quick-witted extempore interventions in Parliament that many had judged him incapable of. (His “suit-boot ki sarkar” jibe was launched then, and stuck, forcing the PM to auction his notorious name-embossed pin-striped suit and adopt the very populism he had previously decried in the Congress).

I recall how, when he referred to the PM as “aap ka pradhan mantri (your prime minister)”, the BJP benches shouted back, “Aap ka bhi pradhan mantri hain (he is also your prime minister)”. RG waited for the hubbub to subside, turned to his hecklers and said disarmingly, “Haan, mera bhi pradhan mantri hain. Lekin kisan-mazdoor ka pradhan mantri nahin (Yes, he is my PM, too. But he is not the PM of farmers and workers).” It was a devastating put-down. The BJP benches fell silent.

This is the Rahul Gandhi the voters of Gujarat have come to see. For the last couple of years he has criss-crossed the country in second-class railway compartments to see farmers (and interact with families along the way). He has sat on the ground in thatched huts and shared meals with fishermen and dalit workers. He has addressed mass rallies in two dozen states. And, he has initiated a number of new organisational changes in the party, including the establishment of an All-India Professionals’ Congress, whose leadership he has entrusted to me.

All these developments have energised the party. These have not been one-off events, but part of a continued and sustained process that has put the ruling party and its government on the defensive.

Turning tides: Rahul Gandhi at Berkeley in California | PTI

Turning tides: Rahul Gandhi at Berkeley in California | PTIThere was so much negativism about Rahul Gandhi, assiduously spread by the ruling party, that people had acquired the perception that he was a young man not yet ready for prime time. But today, when he stands up in the Lok Sabha, or at Berkeley, or in Gujarat, and speaks with confidence on the economic crisis facing the country, with command of facts at his fingertips, with wit and quick repartee, his own performance portrays him in a very different light from the caricature. The narrative about RG is changing because he himself, not any spinmeister, is leading the change.

The problem with RG had been that his own public instincts were previously not very outgoing. He saw a lot of his work as being more effective behind closed doors, within the party organisation, and not so much on the floor of Parliament, or on television. In this, he was true to the tradition of reticent reserve so effectively epitomised by his mother, but out of sync with the demands of the times. In modern politics, a leader needs a public approach, conspicuous visibility and a persona that is seen as accessible by the voters, even if it is only, as in Narendra Modi’s case, through the illusory medium of sound bites on television.

This is what the new RG is achieving, and he is on television not only through sound bites, but tangible actions: visiting farmers in distress, sitting on the ground in solidarity with unpaid sanitary workers, sharing tiffin with families on a train, allowing a teenager to leap onto the hood of his jeep in a motorcade, giving selfies to a young boy on a plane. And, he is on social media in a way he had shunned previously, active, clever, on the ball.

These activities are both spontaneous and part of a systematic and well-thought-out outreach effort, not merely to tap discontent with the policies of the present government (which is the job of the opposition to do) but to develop a new set of constituencies for the Congress. The day he announced the Professionals’ Congress he also announced a new cell to support unorganised workers—hawkers, chaiwallahs, footpath vendors and their kind—who had hitherto had no union to speak for them.

Rahul Gandhi is thinking beyond the traditional categories of caste, religion and region to reach out to Indians in terms of their life experiences. There would have been a time when a Congress leader might have supported sanitation workers as dalits; RG spoke for them principally in terms of their occupation and income. Similarly, his support for the agitating IIT Madras students, whose Ambedkar-Periyar Study Circle was banned, was couched as a freedom of speech issue, not one of discrimination against dalits or against a dalit cause. The dalits are not being abandoned, but their problems are being taken up as national ones, involving principles that affect all Indians, not merely confined (as the BJP likes to allege) to a specific community or ‘vote bank’.

RG sees himself as providing a national voice for marginalised people. He wants the Congress to work to create a ‘support base’ for the millions of Indians who had broken free of the poverty trap but are not yet comfortably middle class. Vegetable and fruit vendors, fisher-folk, sales clerks, auto rickshaw drivers and sanitation workers are all examples of such people. RG calls them “the hands that build the nation” and has pledged them support, with basic rights and government-provided welfare assistance.

He is not abandoning the traditional Congress constituencies, but there is something new and additional in RG’s approach. His interactions with middle-class homebuyers victimised by unscrupulous builders, his support for ex-servicemen denied the ‘One Rank, One Pension’ that the government had promised (and the prime minister had announced), his solidarity with Kerala fishermen battling a trawling ban extended by the Centre, and his speaking out for the small and micro enterprises thrown out of business by the disastrous demonetisation last November, are all examples of a wider and more inclusive Congress politics shaped by RG’s vision.

Critics had nastily suggested that RG was reserved because he was not capable of being eloquent. There were attempts on social media to paint him as somehow slow-witted, especially in contrast to the ebullient and fluent Modi. I used to sit directly behind him in Parliament during my time as a back bencher between my two ministerships in the UPA government, and I knew how false this depiction was. We would chat daily; I found him not just very intelligent but highly intellectually curious. His conversations with me were mainly about books, on which he spoke lucidly and knowledgeably; not only did he read widely but he had a talent for absorbing fully what he had read and synthesising its lessons. In this he is a striking contrast to the comparatively poorly-read prime minister.

Once, at the 2013 chintan shivir in Jaipur that anointed him the party’s vice president, I was seated next to him at dinner and found he was happiest telling me about his then recent lunch with Nicholas Nassim Taleb, the inventor of the concept of the Black Swan, who had come to Delhi the previous week. This is the side of Rahul Gandhi that the public doesn’t know—and that he never chooses to show publicly.

I believe that, as the nation—exhausted by the endless speeches and unending non-performance of the prime minister—pays attention to the alternative, we will all get to see much more of the thoughtful, reflective person Rahul Gandhi is. More important, we will see the Congress party re-energised by a quick-thinking politician with a clear vision for the country, poised and ready to take on the mantle of governance in 2019.

Tharoor is a Lok Sabha member and author.

Source: http://www.theweek.in/theweek/cover/renaissance-man.html