If there is one attribute of independent India which I revel in extolling, it is our “soft power”. I have talked about soft power for over 15 years now in various writings and speeches, and I dare say that the concept (originated by Harvard’s Joseph Nye, and applied by me to India with his blessing and encouragement) is now well established in contemporary discourse about our country.

“Soft power” relates to a country’s ability to attract the goodwill of other nations through its culture, its political values and its domestic and foreign policies. In India’s case, everything in our culture, from cuisine to Bollywood and yoga, contributes to our soft power, as does our democracy, our rich diversity and pluralism, and our constructive role in global affairs. These days it is not the land with the bigger army that wins, but the country with the better story to tell the world. India has, in many ways, been the land of the better story.

But there’s a catch. Soft power becomes credible when there is hard power behind it; that is why the US has been able to make so much of its soft power. Hard power without soft power stirs up resentments and enmities; soft power without hard power is a confession of weakness. Have we, while celebrating our soft power, become a weak power?

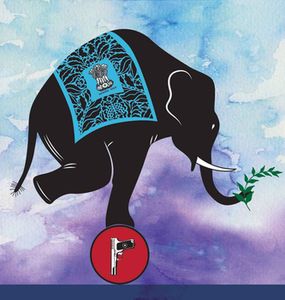

Illustration: Deni Lal

Illustration: Deni LalRecent Indian history offers a somewhat mixed picture when it comes to the effective use of hard power. The 1971 war with Pakistan, leading to the emergence of Bangladesh, remains the pre-eminent positive example, but there are very few others—the repelling of Pakistani intruders from the Kargil heights in 1999 and a swift paratroop intervention in the Maldives to reverse a coup against President Gayoom in 1996—providing rare instances of hard power success. Against these examples are the 1962 China war, the spectacular failures of the Indian Peace Keeping Force in Sri Lanka in 1987 (which withdrew after incurring heavy casualties in an unplanned war with the Tamil insurgents), the hijacking of an Indian Airlines aircraft to Kandahar in 1999 resulting in the craven release of detained terrorists from Indian jails, the repeated “bleeding” of the country through terrorist incidents planned and directed from Pakistan, notably on 26/11 (still unpunished) and innumerable unprovoked incidents on our borders in Kashmir and even with Bangladesh, involving loss of life.

India is often caught in a cleft stick on such matters: it treads softly in its anxiety not to come across as a regional bully, and in so doing it emboldens those who are prepared to test it. As a result it has been noticeably reluctant to evolve a strategic doctrine based on hard power.

Of course, soft power lasts longer and has a wider, more self-reinforcing reach. For China and Russia, Kung-fu movies or the Bolshoi Ballet will win more admirers internationally than the People’s Liberation Army or Siberian oil reserves, even if in each case the latter is what the state relies on. Whether it is the Americans in Guantanamo, the Chinese in Tibet or the Russians in Georgia, it can in each case be said that a major military power won the hard power battle, and lost the soft power war.

So hard power is not enough. But soft power alone cannot solve our security challenges. After all, an Islamist terrorist who enjoys a Bollywood movie will still have no compunction about setting off a bomb in a Delhi market. To counter the terrorist threat there is no substitute for hard power, coupled with skilled diplomacy. We must dissuade those who would do us harm with both the olive branch and the thorn-studded club. Narendra Modi’s recent visit to Pakistan showed that we possess the former. We should also make it clear that we have not abandoned the latter.

Source: http://www.theweek.in/columns/shashi-tharoor/olive-branch--thorn-studded-club.html